Ignited by emerging economic trends and demographic preferences, many cities across the United States, Europe, and other global regions are witnessing a new geography of innovation: innovation districts. Brookings documented their emergence in the 2014 research brief, the Rise of Innovation Districts. This work defined innovation districts as geographic areas where leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and accelerators. Districts are also physically compact, transit-accessible, and offer mixed-use housing, office, and retail.

Since then the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Initiative on Innovation and Placemaking has conducted research to advance this emerging practice. In the paper How Firms Learn, we analyzed how firms and other institutions are altering their processes for innovating. In the paper Innovation Spaces: The New Design of Work, we observed how many innovation spaces are now being designed to reflect the increasingly collaborative and cross-sector nature of innovation. We also conducted deep engagements in burgeoning innovation districts, such as in Oklahoma City and Philadelphia, where, in concert with local actors, we developed strategies for accelerating their innovation ecosystems. Lastly, working with the US Conference of Mayors, we developed a handbook to support city leaders in their desire to facilitate this emerging geography of innovation.

Drawing on this and other work globally, we have developed these 12 principles to guide how innovation districts are to grow and evolve—a process that requires cities to take an integrated approach:

- The clustering of innovative sectors and research strengths is the backbone of innovation districts. The concentration of innovative sectors and research strengths is what drives innovation districts from the start. Rather than government attempting to pick industry winners or developers focusing on a real estate play, districts thrive by concentrating and leveraging their city or regional economic strengths. For example, Oklahoma City’s strengths include health care and energy, while in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, it is precision machinery. Bottom line: Cities need to grow their own firms and, when possible, recruit from elsewhere.

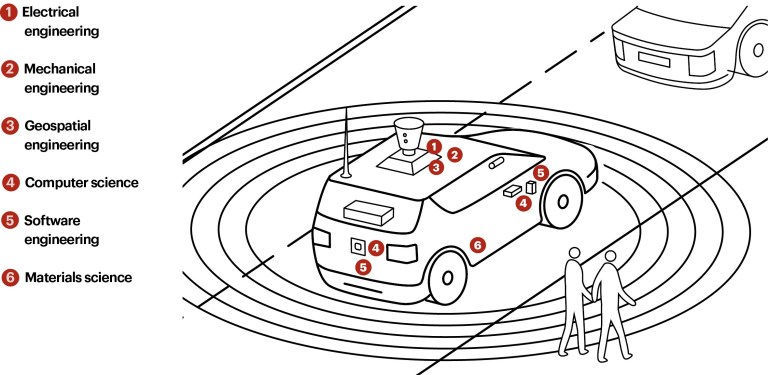

- For innovation districts, convergence—the melding of disparate sectors and disciplines—is king. Many economic developers think about the world in terms of industry verticals (e.g., agriculture, aerospace, health care). But innovation platforms—IT, new materials, robotics—are technology enablers that serve many industries. As hubs of research and next-generation technologies, innovation districts are more aptly defined by these horizontal platforms than by sectorial silos. As such, district stakeholders need to build their capacity to connect seemingly dissimilar industries through collaborative research, conversation, and cross-cutting technologies.

- Districts are supercharged by a diversity of institutions, companies, and start-ups. The strength of innovation districts comes, in part, from this eclectic mix. Districts that are largely comprised of large institutions often lack the accelerated innovative growth that small, nimble firms provide. And districts characterized by a density of start-ups have fewer opportunities for well-funded partnerships and alliances. The “magic in the mix” comes from aligning incentives between these and other public, private, academic, and civic institutions.

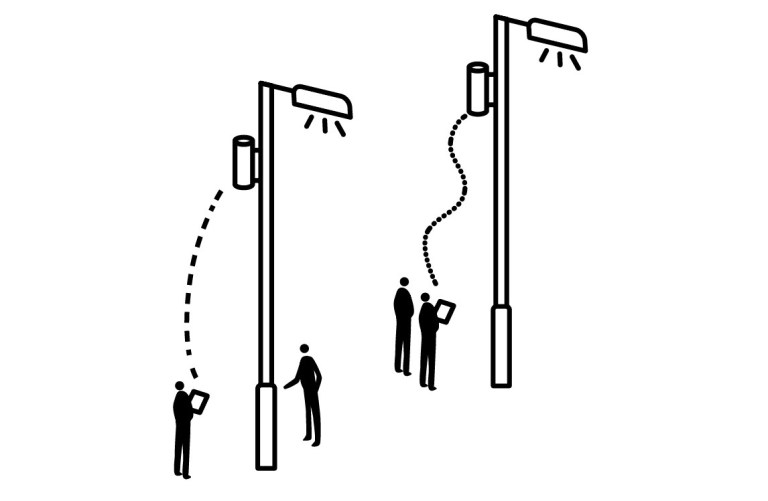

- Connectivity and proximity are the underpinnings of strong district ecosystems. A well-connected district is paramount to its success—transit, bike paths, sidewalks, car-sharing, and high-speed fiber. Identify gaps and invest wisely. At the same time, districts should measure their success by steps not miles. The experience of proximity—or a physical concentration of firms, workers, and activities—is what differentiates a “buzzing” district from a boring one.

- Innovation districts need a range of strategies—large and small moves, long-term and immediate. Innovation district development requires a mix of large investments (e.g., in transit, high-speed fiber, venture and other capital funds) and smaller strategies (e.g., reactivating a neglected park and programming spaces). These approaches are complimentary: Large-scale investments set the foundation upon which other activities can be layered, while short-term, community-led processes can inform bigger and lengthier undertakings and create crucial momentum.

- Programming is paramount. Programming—a range of activities to grow skills, strengthen firms, and build networks—is the connective tissue of a district. A major misstep is to undervalue programming within and across the district, both indoors and out.

- Social interactions between workers—essential to collaboration, learning, and inspiration—occur in concentrated “hot spots.” A handful of social hot spots in a district will likely punch far above their weight in terms of building community. They may be organic, like Silicon Valley’s legendary Walker’s Wagon Wheel, or designed, like Venture Café near the MIT campus. Districts should identify, analyze, protect, and support such exceptional places.

- Make innovation visible and public. Daylighting innovation in public and private spaces helps inspire curiosity in aspiring innovators, start conversations between neighbors, and convey the story of an innovation district to potential recruits or investors. It also transforms public spaces into “living labs” to test prototypes. To help further, activities like hackathons (a sprint-like event encouraging collaboration generally on software/hardware development), symposiums, and health clinics, which typically occur indoors, might accomplish more in the public realm. And finally, greater transparency at the ground level of buildings allows pedestrians to connect with the innovation activities inside.

- Embed the values of diversity and inclusion in all visions, goals, and strategies. Innovation districts not only promote new technologies, they grow a range of new firms and new jobs with living wages. At a time of rising social inequality, innovation districts must become an avenue to economic opportunity for city residents—particularly for those in nearby neighborhoods that struggle with poverty and disinvestment. But growth alone is not enough. Only through intentional training, hiring, business development, and placemaking efforts can districts cultivate new local talent, encourage more diverse ownership structures, and help address poverty and disinvestment in surrounding communities.

- Get ahead of affordability issues. Successful districts can, over time, drive up market pressures, impacting the ability of start-ups, maturing firms, and neighboring residents to remain in these areas. Smart districts respond early, getting ahead of the curve through a range of policy moves and strategic projects that preserve affordability and the diversity it engenders.

- Innovative finance is fundamental to catalyzing growth. Most innovation districts require new finance streams to advance innovative and inclusive growth without straining existing and limited resources. As districts will likely receive less funding from states and the federal government to support their efforts, creative financing tools—including ways to leverage city-owned and district assets—should be explored with an eye toward sustaining financing over time.

- Long-term success demands a collaborative approach to governance. An innovation district’s work ethic and culture is “collaborate to compete.” A bottom-up horizontal governance model—involving business, academic and civic institutions, government, workers, and residents—can best orchestrate what must be done collectively: Identifying assets; design, finance and strategic initiatives; public space management; and evaluating progress.